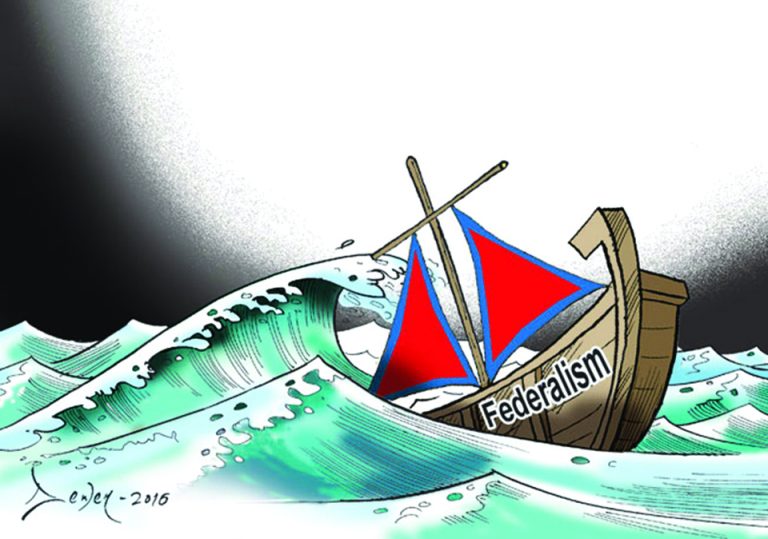

Nepal’s fiscal policy for 2082/83 exposes deep cracks in the country’s federal system, raising concerns over political stability, governance inefficiency, and stalled development.

Despite the constitutional promise of a three-tier federal structure, the reality remains a system dominated by centralized control. Over 64 percent of government expenditure still lies with the federal level, while provincial and local governments receive only 9.9 and 25.9 percent respectively. Revenue collection is even more imbalanced, with the federal government controlling 92 percent of total revenues.

Nepal’s federalism was designed to empower local governance, yet poor implementation has weakened state institutions. The budget for 2082/83 fails to deliver meaningful support for provincial or local institutions, offering little in the way of capacity-building programs or reforms to help these bodies become independent, efficient, and responsive to local needs.

The country’s political instability has only worsened the situation. Frequent changes in leadership, driven more by opportunistic alliances than policy commitments, have led to weak governance. This revolving door of politics has kept Nepal stuck in a cycle of short-term decision-making, undermining long-term growth.

The economic picture is also worrying. Nepal remains heavily reliant on remittances, which make up over 25 percent of GDP, while public debt has climbed to 40 percent. The trade deficit remains large, and over 300,000 workers continue to leave the country every year in search of employment, reflecting a lack of domestic opportunities.

Capital expenditure has been inconsistent, ranging from 3.7 percent of GDP in 2071/72 to a peak of 11.4 percent in 2077/78, before falling again to 7.8 percent in 2080/81. This inconsistency signals poor fiscal planning and limited project implementation at the local level.

The federal grant system also remains flawed. Conditional, equalization, and matching grants managed by the federal government often fail to align with local needs. As a result, sectors like healthcare, education, infrastructure, disaster management, and environmental protection remain underfunded.

The new budget talks about governance and anti-corruption, but these are unlikely to succeed without serious institutional reforms. Local and provincial governments lack the legal, administrative, and technical capacity to carry out key functions. Without clear roles, proper training, and protection from political interference, they will remain weak and dependent.

Donor-supported programs targeting local governance are also falling short. These efforts lack coordination with broader government policies and fail to address structural weaknesses in federal implementation.

Experts suggest that real reform must include civil service restructuring. This includes merit-based recruitment, performance-linked incentives, and strong checks against political manipulation. Only with a professional and autonomous bureaucracy can Nepal move toward effective decentralized governance.

Nepal’s current system risks becoming a case of predatory decentralization, where the appearance of local empowerment masks the continued concentration of power. The government must act fast to clarify governance roles, reform institutions, and support subnational development, or risk watching its federal system slide into dysfunction.